If you know anything from horror, you’d know that Stephen King has two sons, both of whom are also authors. One of them, Joe Hill, made his name in shorts and comics before revealing his identity. Hill’s 2005 collection 20th Century Ghosts featured a twenty page story called The Black Phone that was, among other things, about a haunted telephone. Twenty pages can fit a lot of detail but, as a film, The Black Phone is proof positive of the power of converting short stories rather than full novels into movies – there’s a lot more room to breathe. Apart from the basic concept, The Black Phone is made up from near whole cloth. There’s so much going for it that it’s difficult to feel bad for Scott Derrickson’s (Doctor Strange) unceremonious ouster from the Marvel Cinematic Universe: some men were meant to not only play, but thrive, in the world of small budget horror.

In 1978, Finney (Mason Thames, TV’s Walker) lives in a small Denver town that has been terrorised by a child snatcher known only as “the Grabber” (Ethan Hawke, The Northman). When Finney himself is grabbed, he’s left in a basement that is nondescript except for a disconnected black phone that seems to ring sometimes — and ghosts are on the other end. While his psychically inclined sister Gwen (Madeleine McGraw, TV’s Secrets of Sulphur Springs) desperately tries to find Finney in her dreams, Finney marshals his courage to listen to the voices on the other end of the line in the hopes that they can help him escape.

The Black Phone is beautiful in its simplicity. The 2004 short story was not a period piece, written as it was in a time where mobile phones were not ubiquitous, but the shift to a 1978 setting seems natural without leaning on any kitschy gimmicks. The complete lack of stranger danger preached by the children and adults — in a town where five boys have gone missing in a relatively short period of time, no less — is something that seems baffling now, but the distance of time means that the shrugging nature of the community becomes somewhat credible.

Beyond this, The Black Phone is a three hander – two child actors with Hawke as their fulcrum. Thames’ role is largely reactive, but the confined space that his story is told in allows him to develop a relatively muscular character arc; importantly, Thames can carry scenes on his own, because he’s not always talking on the phone and is only occasionally treated to a jump scare. The construction of the basement escapades is layered, and The Black Phone sets up many elements that it knocks down with a rare sense of satisfaction.

The crowd pleaser of the film is the vaguely heretical Gwen, whom McGraw imbues with an eye rolling sarcasm that only partially shrouds her insecurity. McGraw delivers all of the best lines from her scrying shrine, and provides the balance that the movie needs to keep its momentum up — Derrickson could have gotten away with delivering a bottle movie, but what we end up with has more texture and satisfaction as a result.

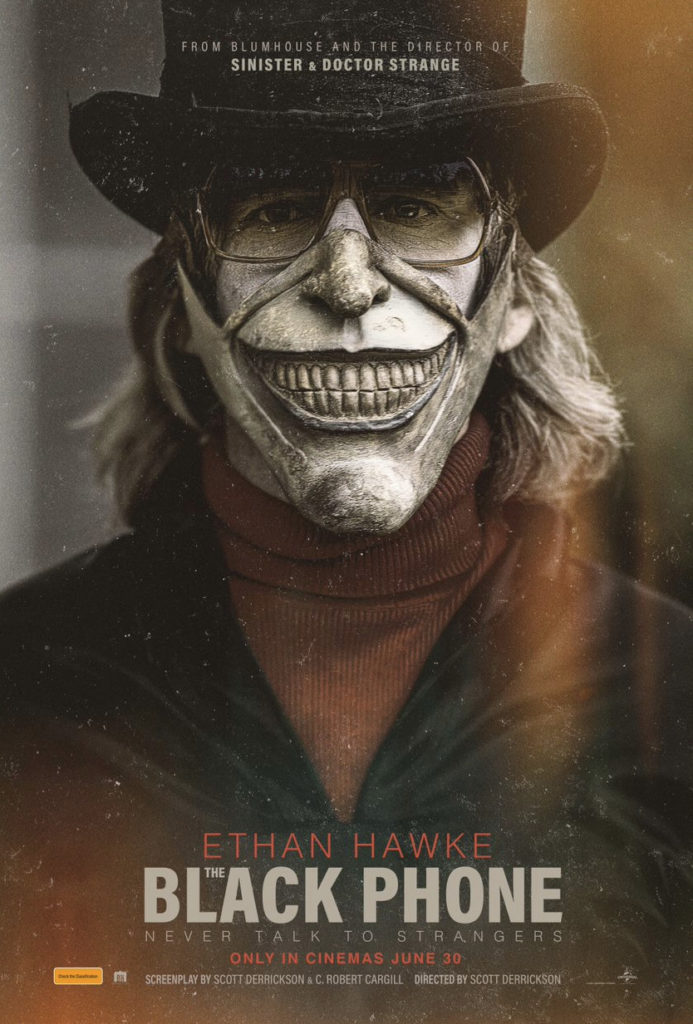

Yet Thames and McGraw would have no need to rebel were it not for Hawke, whose face is very rarely seen. Wearing a series of modular mask pieces, Hawke’s Grabber is devilish and offputting but, more than that, ambiguous in a way that neither Hawke nor Derrickson is interested in explaining. We know that the Grabber grabs boys, imprisons them, and kills them, yet we never learn why. He’s creepy because he defies explanation. He doesn’t fall into easy traps of child molestation, and there’s no dark past to be plumbed. What you see with the Grabber is all you get, and Hawke is by turns terrifying and pathetic. All you know is that he needs to be stopped, and that there will be no quarter.

The script, care of Derrickson and long-time collaborator C. Robert Cargill (Doctor Strange) is an ornate jewellery box. The parallels between the Grabber and the siblings’ father (Jeremy Davies) are highlighted without being hammered home, and themes are there to be taken and ran with or discarded as the viewer desires. There are questions of faith, of family, of the utterly psychopathic degree of violence the children of the seventies were apparently willing to commit against one another, and what answers we are offered are intriguing — and set, no less, against some choice musical cuts of the seventies without being gratuitous.

The Black Phone is an unrelentingly dark little movie that embraces its supernatural roots and retains the capacity to surprise. Far outpacing its humble beginnings as a short story that may well have existed only for its (satisfying) punch line, The Black Phone is an elegant horror film for those who aren’t too squeamish to see children in peril.

The Black Phone opened in Australian cinemas on July 21, 2022.

Directed by: Scott Derrickson.

Starring: Mason Thomas, Madeleine McGraw, Jeremy Davies, James Ransone and Ethan Hawke.