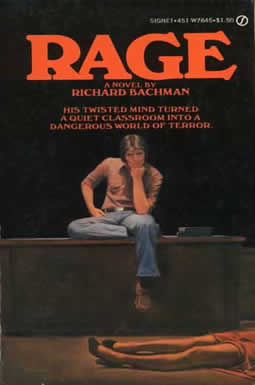

More can be said about Richard Bachman than can be said about Rage, his secret and forbidden debut novel, pulled from the shelves during the early days of school shooting contagion. Written well before school shootings became so common that it is difficult to tell them apart, Rage is a Stephen King piece so early that he was in high school himself when he wrote it.

Richard Bachman is a pseudonym created by Stephen King for a variety of reasons depending on what King feels like telling the reader at the time: Bachman was a way for King to put out more books per year, separate from the King brand; he was a way to get rejected earlier works published after some retooling; he was a chance to see if, eventually, Bachman's books were able to be read, sold, and appreciated separately to the King name; and, to quote 1996's "The Importance of Being Bachmanâ€, an imprint for books written "in a Bachman state of mind: low rage, sexual frustration, crazy good humor, and simmering despair.â€Â

Rage is not a cry for help, but rather a bitter study of the powerlessness that teenagers can feel, and the most artificial power they can conjure to battle that: a warm gun.

High school senior Charlie Decker, already in trouble for assaulting his chemistry teacher, kills his algebra teacher and holds his class hostage for an impromptu group therapy session. He ruminates on why he's like this, seeks input from his classmates, and hectors Ted Jones for not playing along.

Rage was originally called Getting It On, a hilariously dated piece of slang that holds more meaning and character than the bland single word that it ended up with. The title matches the content, however, because Rage is a one note book with dubious psychosexual analysis at play: Charlie once had difficulty maintaining an erection, so he feels he must be latently homosexual. You can pretty much put a lid on it here, because that's all you're going to get from Rage.Â

Even if most of Charlie's classmates come to sympathise with him, it is difficult for us to: after all, he unambiguously killed two teachers with no provocation. King tries to make us understand Charlie, but nothing can justify his headspace. He's a loathsome character and none of his classmates endear themselves to the reader, either. The mercy of Rage is that it is brief.

In his slightly rambling and occasionally equivocating essay "Gunsâ€, King does not say that Rage is a cause of school shootings, but rather a potential accelerant, and so he went to the effort of ensuring it would go out of print. He doesn't see this as censorship because he did it voluntarily, but realistically there's no problem with withdrawing it because nothing of value is lost. It's an inauspicious beginning to Richard Bachman's career, no sweet to go with the bitter, and obscure even in the context of one of the most published authors of the last four decades.

"The Importance of Being Bachman†does not reference Rage in the slightest. It no longer exists. If you were unable to get your hands on a copy of Rage, you could happily skip it in the course of a tour of the King canon. This Constant Reader has only ever seen two completely intact copies of The Bachman Books, and one of those instances was such an extreme case of dark serendipity that it could never happen to anyone else.

It is best that Rage is only tangentially linked to the King name. Some of the Bachman Books are good, although King is less concerned about their artistry and more that he enjoyed writing them. Rage is a dark work, yes, but also a tacky piece of pop psychology that owes more to King's lifelong fascination with Lord of the Flies than to entertaining audiences outside of teens who wish that they were disenfranchised.

No Responses